Until you come up blue

It was summer, maybe ten years ago? My brother and I borrowed my mom’s tiny gold car and drove north two hours to the shallowest of the Great Lakes on a day that is what you think of when you read the word ‘August’. Sun saturated, dizzy warm, air easy with a tang like pennies. Lake Simcoe stays waist deep for kilometres out from shore, we staked a piece of driftwood down into the sand to tether the plastic ring of a six pack to and bobbed with the beers and the sailboats at anchor just past us. We swam for hours. Headed home with the sun sinking in the rearview, windows rolled all the way down, my head resting on the door, warm air washing over my face, Carl took out a cassette tape to play in the stereo. A tape player was the only customization my mom made when she bought the car.

My dad was a DJ my whole life and is in the habit of making mixes, first for work, then for himself. The tape my brother popped in was called MIKE’S FAVS, labelled by my dad with his home office label maker, and the first time we’d heard the tape, knew of its existence, which rocked us into belly laughs in the back seat, we were on the way to my uncle’s funeral.

Late spring, the country that started to unfurl from the city we left turned the first clean shades of new green. We’d found it rifling through the centre console between the front seats, initially disbelieving, not that he’d made the tape but I think at the secret of it. We were new to the point where you start to realize your parents have had so many different lives before they all inverted, shrunk to revolve around you. We hadn’t really recovered, our cheeks damp with tears and chests still heaving with euphoria and laughter that only quit because we didn’t have air enough to maintain it, when the opening song blasted its ephemeral first chords (we’d cranked the volume in anticipation, reaching over my dad who was driving).

Faded, echoing synth before the song even starts, gently shaking percussion, catching you in an eddy toward a voice that somehow starts on a deep intake of breath,

Her hair is Harlow gold

A ghost, a very sexy ghost, breathing all over you,

Her lips sweet surprise

Then an electronic drum beat that kicks in to speed you to a place where you forget where you are, ever were, before you started listening,

She’s got Bette Davis Eyes

There are very few songs that literally arrest me, completely, make me so immediately happy but also, crying. That day in the car, both days in the car, we were HOOTING. Screaming, shouting, equal parts ecstatic, amazed, happy. It was so bizarre, this song, this song? I hadn’t, at that point, heard it more than a handful of times. Now I play it whenever I have control over speakers. Number one on the tape, dubbed perfectly, my dad mastering all the mix levels, and he just gave us a little shrug, impervious, before his face cracked in a grin and a “What? Whaaat?” without moving his eyes from the road. I remember my mom singing. We all started singing. In our funeral clothes.

When I heard that my parents were coming home, that the ship they were on got permission after so many failed negotiations with so many other countries, to dock in Fort Lauderdale, I played the song. I cried. In a lot of ways it’s perfect for Florida, for sun shifting across water, tasting salt in your hair after it’s dried from the ocean. It’s an insane song, too, I know that, but it’s appropriate for anything. Grief, joy, lying on the floor alone in a middling grey mood, driving, god it is so good for driving. The part where Kim Carnes hunkers down and growls Rollllll you like you were dice will chomp my heart and yank my breath out from my chest like a rug.

My dad can be as sensitive as I am, and the intimacy of this song on the tape, of this song at all, picturing him cycling through all the feelings it fits, listening to it, has lodged in me so deep that if you pressed your ear to my chest I’m sure you’d hear the persistent kick drum anchoring it, tune with my heart.

Tim Hardaway Jr. has been hosing down manatees. For two weeks now, at least that he’s recorded, a pair has come trundling up close to his back dock (like a back deck, I guess, when you have direct canal to ocean access), so close you can make out the darker freckles and spots on their soft grey skin. He takes a garden hose and, I imagine this part, unloops it slowly from where it’s gathered at the top of the dock or maybe up closer to his house, giving himself enough slack. He goes to the edge of the dock and aims the nozzle out, squeezes the triggered handle, lets the water out in that initial sun simmered warm stream, the kind you got so grossed out by as a kid when you went to drink from the thing. It hits the water and the manatees tilt their wide, slow axis, make their way over to close the 2ft gap. They just sit there, under the stream, bubbles around their heads.

In another video, one’s come closer, right up to the end of the dock. Hardaway Jr. has removed the nozzle and let the hose hang from his hands, dangle down into the water. The manatee has its nostrils right up against the bubbles, is circulating its diminutive flippers to stay suspended in place, which doesn’t seem difficult for something so big and buoyant, so maybe it’s excited. But manatees drink freshwater, so maybe it’s chugging.

In every video, Hardaway Jr. is silent, but his hands don’t shake, the recording steady. I imagine it meditative, because you can’t see another soul around in what you can make out of the background. He’s just there, hosing the manatees for long, beautiful stretches, sun glinting off mineral green water.

My new routine varies. Dogs go in the morning, growing warmer now, cutting across an empty soccer field, down to the big park at the end of the street. Watching for the pair of hawks there that have come to build their nest and decimate the squirrel population. Coffee, work, write, get up and touch my jewelry in its ceramic dish on the dresser, the old cigarette tin in the hall overflowing with change, any other object scattered around that I’m communing with more if only to remember the far flung places most of them came from. Dogs go again after lunch. Water plants, watch email, watch the windows, watch my nails grow in. I talk to my parents, every day like when they were gone (I was going to write “at sea” but life is theatric enough), but there’s no more five second delay on the satellite call, when I would hear them answering a question like it had hung in the distance between us, I guess it had, now it’s just going through to the landline they’ve had since I was a kid, the only number I still have memorized. Dogs go again when the light starts to get long.

I’ve made a gin and tonic a handful of times, mostly to take a slow minute to use the vegetable peeler deliberately around one end of a lemon for rind, oil shining on my fingers. I talk to Steph, her voice an easy metronome if I’m restless. Sometimes I write, somehow it feels different than what I did in the day even if I’m sitting in the same spot. Some evenings it’s getting in the bath while it’s still light out, watching the sun filtering through two rows of glass bricks and pass through steam lifting off the water, Tony Soprano’s voice coming from down the hall as Dylan gets through season two because he got tired of waiting for me to pick up from where we left off last winter.

I was in there last night as soon as the sky split, season’s first lightning, and rain started. I felt so sated, then guilty, then coaxed myself back into ease. I finished the first book I’ve been able to read through all this in there, Ordinary Dogs by Eileen Battersby. She’s an American-Irish Writer I found by accident, buying her first novel, Teethmarks on My Tongue for Dylan.

I watched him work through it so closely that it slowed him down and when I pressed him for how it was he’d said, “Good”, and I started in, wondering why he hadn’t been more enthused. I realized pretty soon it was a book written for me. When I told him, he shrugged and said he’d realized it right off, but felt he should finish. It’s all horses and the American South, a woman growing up who heads to Europe and sort of fumbles her way through places and people bucolic and sinister. I loved it so much I found the author’s email, via the Irish Times where she worked. I had a draft going in my Gmail for two years because I didn’t just want to tell her I loved the book, I wanted to be so casual but sincere about it that we might have some kind of correspondence. I’d look her up every few months to see if she had a new book on deck and when I last did I saw her obituary. She’d died in a car crash last December. I bought her first book, the last I’d read from her, when I found out.

I was crying in the tub, because the book was so good, but because there’s a lot in there about her reluctance to get her driver’s license and when she does, how many wrecks she’d witnessed in Ireland. She got the license to be able to drive her dogs to the beach, to the back country, and to the vet because they seemed to get in a lot of trouble. Also because it’s about life, the way your relationships slow or accelerate the years, how you can see whole entire decades through the people or things you love and they’ll never feel lost that way when you look back.

I wish I’d sent the email. I found an article about her after she died, that said she was wary of praise, that she didn’t often write back to fan mail when she got it, so it’s likely I never would have heard back or had the relationship I’d made up with a stranger, but she’d’ve read it, whatever it was worth. I still haven’t deleted the draft, and I probably won’t, because it’s become something else. A reminder that there is literally no good time for anything, and no bad time for the same. There’s only time against a shifting scenery of whatever someone is experiencing, until time stops and the background, everything, drops.

John Prine and Bernie, basketball, the economy, hundreds of thousands of lives. This thing is bringing a lot to accelerated ends. Some we could do without, where false trust has been placed, for one, in bloated and cannibalizing systems. How government has slashed and hacked at healthcare, whatever country you’re in, for a long time because the inevitable seemed so far off if not impossible. The inevitable that’s here, a virus that sucks the air, the life, out of people, out of a lot of what we found comfort in, whether its depth was like minnows spinning in the shallows or past where light gets to, doesn’t matter.

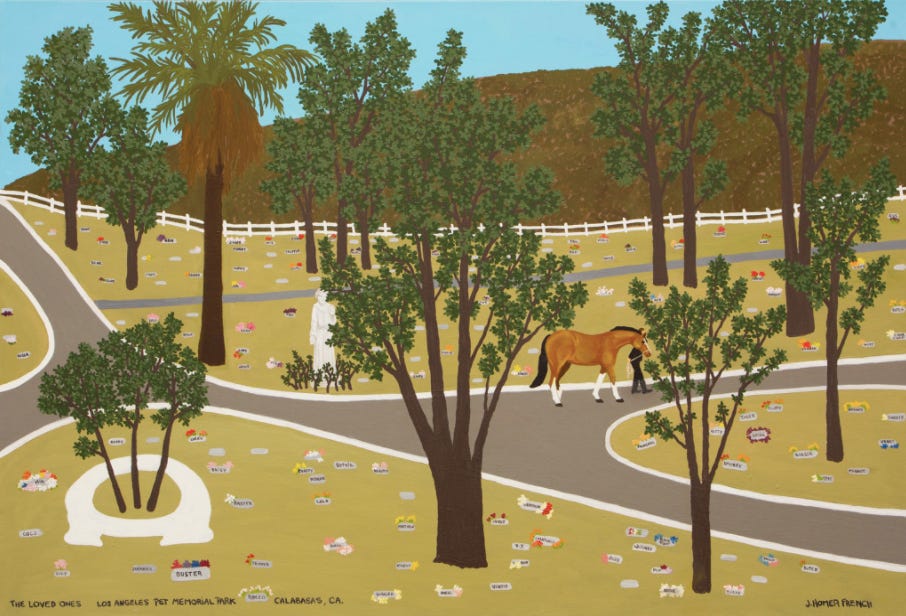

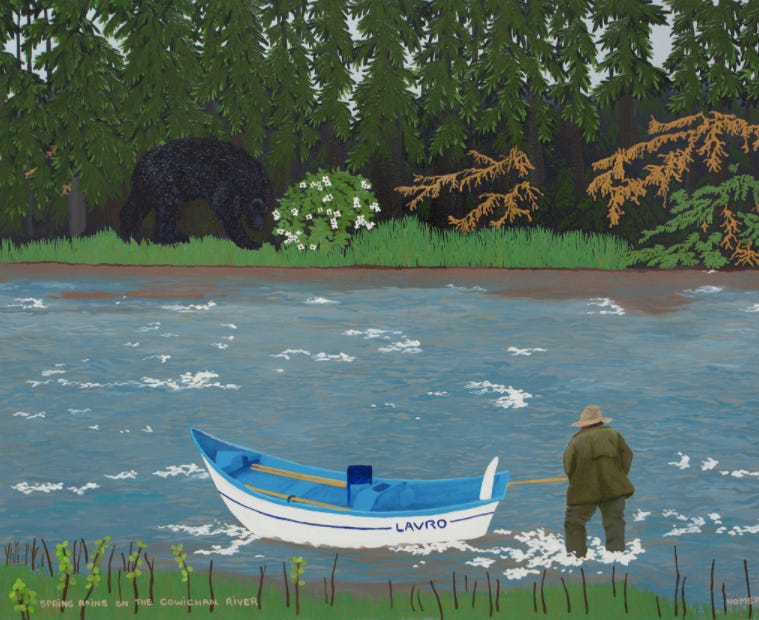

We see it reflected back to us even when we drop out, slink away from the news for stolen snatches of time. My friend Louis asking for pictures of people’s house plants because he was feeling so low, me running all over the house to send a lot, too many, him deleting Instagram before he got them. My aunt, who lives way out in the country beside a river which is right now grown three times its size, spending the day making fabric masks to wear, I think, down to the water. Sending pictures of Jessie Homer French’s flat and exploding paintings to Greg, the only artist I do not feel embarrassed to be dumb around, how they have whole and quiet lives in them.

How we are all making bread? Or forced to think about making bread because someone we know is. How we all aren’t sleeping, or if we are, then we are dreaming with such violent lucidity that we wake up wrung out from the very act of rest.

There’s no way to get away from this, and as much a weight dragging around your waist, your temples, all your soft parts it can be, to look and to see that, to write down, just for yourself, what you are doing, what you’re seeing, how you’re getting through the days, is an exercise in taking history, this whole thing and your own, by the hand at least. A small measure of control.

Standing outside in lineups, 6ft spacing automatic, everyone with their faces turned up to the sun. It’s slow going, one in one out, getting Purel’d by staff in the entryway. The days are the only things starting to turn wide open, blue sky you have to squint at.

In each line everyone aware, intensely, of what it felt like to be out, to have the wind cutting up from the lake fling each side of our unzipped jackets open, to feel warm in the sun again, to fantasize about feeling even warmer when no one is sure what those longer days will look like, how light might be rationed, whether or not we’ll be permitted into it.

I’m getting good at watching the shoulders of people from behind, for the instant they slump when it’s their turn to head for the door, step into the shadow of the building and out of the sunlight, feel it when my own do the same. Our bodies, even in terror, instinctively lifting to light. We don’t ever lose that.

I just restumbled(it’s a word I swear) upon this in my inbox. Katie, you’re so damn good at this.