Try for tender

Ten days into the new year and its foundations already shaking. With how fraught everything can get to feeling it was like a slow, hand warmed piece of sea glass—your fingers going over and over and over the slip and softness of water blunted edges—pushing into my chest while watching six separate faces of commuters, each in their own small universe, tilt their faces to the sun coming in the streetcar windows and close their eyes. January is always hard. Always edged with salt. The trace of it on your boots, winter coat, like rings forming in a tree trunk. To take stolen seconds from the bite of it, to soften and prostrate yourself to time, feels a protection.

In the locker room the night before, looking down at Anfernee Simons sitting there, towel over his knees and chest still gently heaving from the court, I lost hold of the thread I was counting to follow in talking to him. Slipped from my hands so fast I felt winded. He is so young. Wide open and waiting, watching me for the end of my question to become clear. The trust of it, that I would conceivably get there, that he would answer, the closeness of those initial seconds, crystallized to ringing how everything is held in the extreme fragility of any given moment.

It wasn’t his life unfurling before me because nobody can see that, but the promise of it. Rubbermaid tubs of ice big enough for legs scattered around the locker room floor, chafing dishes of meatballs and penne on folding tables in the centre of the room, the thrumming huddle of writers and reporters waiting for Melo, Simons breathing, my brain repeating speed, speed, speed hoping the word would catch a train of thought to hop.

“Speed over physicality,” I finally blurted, “how do you protect yourself?”

How does anyone.

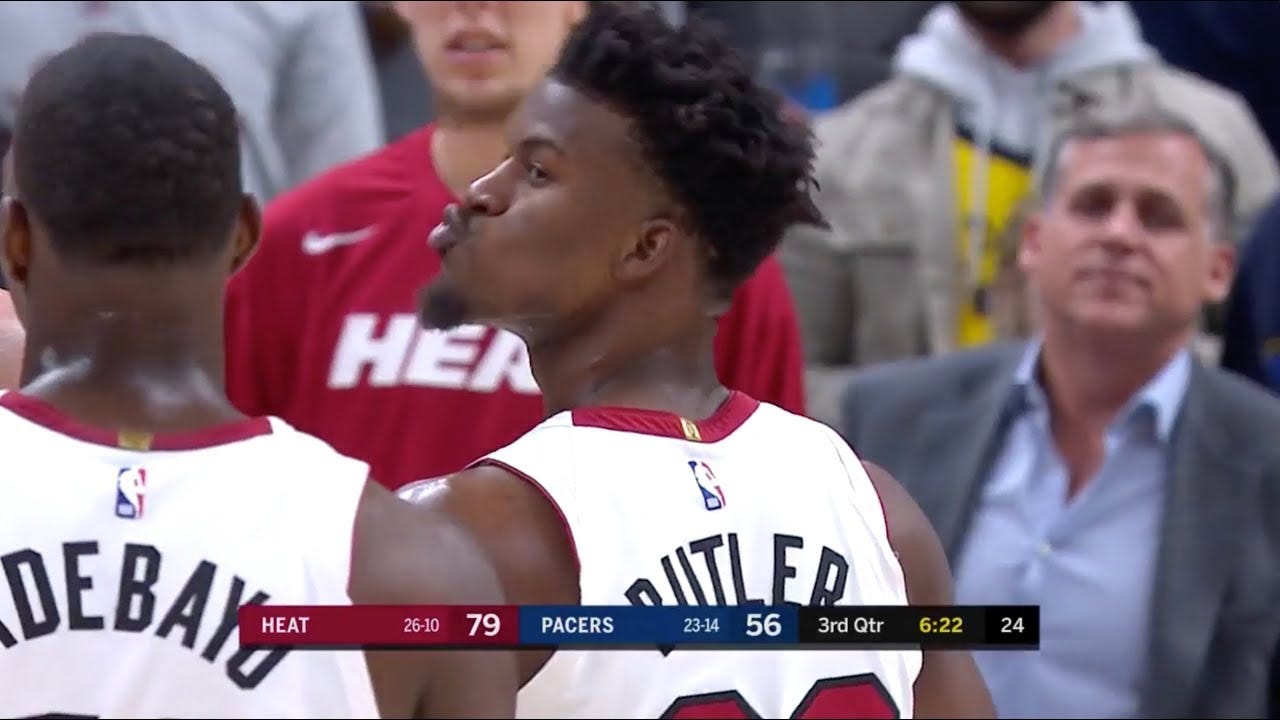

The idea of clapping hard behind Jimmy Butler’s head is a bad one. Most obviously, you are applauding him walking away, and I can’t think of something I’d want less. Then there is how rude and sneering of a gesture, but also how hollow. T.J. Warren does it—and you can see it on his face—in that split second you have to heave yourself back from what is going to be a bad decision. He passes that place, fuelled by frustration or the disconnect that being in a moment can bring, like a warped glee, and tromps out to finish the long walk down a short stretch of court.

But to get the whole sequence you have to start where it did. It’s like a piece of music, a slow crescendo, a rising pace, and when you think it has concluded there’s a coda that sends you right back.

Fittingly, the Warren-Butler dust up started like a dance. Meyers Leonard hands it to Butler, who starts to make his regular run down the lane. Before Warren enters stage right know that the Pacers are down 23, but there is slightly more than half left of the 3rd quarter, and after that, another entire quarter to go. But here comes Warren anyway, grabbing Butler to both sides of his body and spinning him with his own momentum. Jimmy, of course, knows, and like any talented dancer he leans into the spin. The force he has created for himself sends him square-chested and towering right back into Warren. The whistle is fast. Blown by vet Leroy Richardson who I learned was an underwater sea surveillance specialist in the Navy before taking up the stripes, so he understands pressure on a body.

Everyone looks worried. Myles Turner is just trying to carry his summer energy into January and Sabonis looks like he cannot quite settle on how best to make his limbs soothing draped this way or that over Warren. Butler is being walked backward. He veers a few times, out and back, pushing up against a big, suited security guard who holds him for a few seconds, hands turned tiny against Butler’s body. Bam shows up, Jimmy sits down. The double tech call comes, Warren for a split-second looks on the verge of tears. Then Butler is up and laughing, walking slow down the court boxed on all sides like a racehorse by its pacers. He says something friendly to Nate McMillan and stands at the courtside line, waiting to inbound. Here, if you think things were forgotten, you would be wrong.

There is a tell, a big one because it’s Jimmy. He is dancing very slightly. Doing this little bop and shimmy with his shoulders, his head. If he was still then the momentum of what came moments before would be over, expelled, but the charge of it is latent in his muscles, his smirk. He keeps dancing while passing, in, to Kendrick Nunn. Nunn takes it away and Butler stands still, he knows Warren will come to him, is already leaning over so when Warren gets there he takes the entire weight of him. Butler gets the ball back on an outside pass he has to bend out and down at the waist to catch, pivots up on one leg, then out on the other, Warren won’t give him room. Butler is now just waiting, he already knows what he’s going to do but he wants Warren to be at the exact right tilt for it. The poor guy does it. He drops his arms in that Weekend at Bernie’s dead weight way to guard, his body perfectly primed for what’s coming. Butler was already crouched but he drops his shoulder and slams forward into Warren’s chest, stands and starts to turn, staring back at Warren before tossing the ball down behind him, as if to show that wasn’t ever the point.

When Warren follows Butler he is forced to go exactly as fast as Butler is walking away from him, another way that Jimmy wins, even while Warren applauds. Warren isn’t stopped by Butler, but you have a sense that if at any second Butler were to turn around, Warren would freeze in his tracks. It’s a ref that sends him out, Ts him up, and when Jimmy does turn it is with plenty of room between them.

Butler has been thinking about this. Not consciously, because it is so quick, but in the way I feel you would always be bound to lose to Butler when it comes to having the most rewarding and infuriating gesture ready, done lightly, so airy it escapes any situation’s gravity. Careful to remove his mouthguard first, and careful to get the flourish of elongated fingers right, Butler blows a sweet kiss to Warren. He does two with his hand as a chaperone, then turns away and does several in quick succession with Jessica Rabbit lips pursing over his shoulder. You could slow it down and play The Zombies ‘Can’t Nobody Love You’ over the whole thing and it still wouldn’t get much better.

But then Warren does it, the last thing he should have in response to such poetry. A gesture of total futility, out of full body frustration because he knows he has been tenderly torn to ribbons—he flips Butler the finger. Oof. The Pacers all know it, quietly offering Warren their hands in low, non-attention seeking fives as he heads toward the tunnel, while Butler’s teammates crowd and trail him, each made slow and lazy with triumph. Kelly Olynyk continues to chew gum with his mouth open.

Kelly Dwyer of The Second Arrangement put it this way,

Jimmy Butler has a way of looking at this league like the rest of us before cutting toward what’s right, it’s why he’s beloved.

You can dislike Jimmy Butler, but you can’t hate him, because there is no one in the league as remarkably, vulnerably themselves than him.

With Warren, could you honestly have pictured Butler placing a hand on him? I can’t. Either Warren would go to touch him and the entire Heat roster would be on him, or Jimmy would hit him with some kind of Muay Thai kick, out of nowhere on the chin, and keep walking away. But the more realistic thing is the one that happened. It’s Jimmy Butler knowing the exactly correct thing to do, with flourish. If you don’t like him, it is for this flourish, it’s not for how intuitive, and how disarming in that insight, Butler can be.

And Miami Jimmy is just about final-form Jimmy. It is a Butler who is happy, and happily dogging the cameras, the crowd, divvying up these moments of frustration and delight, the timing of which are so precise they can be cutting though they lack the heft of cruelty. He can’t be anything other than himself now, but free from the frustrations of previous seasons. The outbursts toward teammates, toward a team system, that always felt like Butler was short the valve for which those frustrations would benefit rather than some other noxious simmering, are gone. In Miami, the franchise and the physical place, a lot is laid bare. Pat Riley’s strange, more or less body shaming team system fits someone who has always been as candidly aware of his body as Butler has. And in a city slowly sinking, where sun drowns streets that will sooner than we think be submerged in seawater, you’d have a hard time finding people in more layer than just one and sheer. You breathe and you feel the mangroves, the tilting palms, fried plantains and the pastel paint peeling back from the deco buildings in South Beach all snaking into your lungs. Even in sunglasses you can’t help but squint. Hardly any cars have tops on them. Buildings are made of pink marble, glass, gold framed, opulence as a testament to itself, opulence that will shine like gator teeth under brackish water when the swamp takes everything back. The place is all posturing, ease, tender as the belly of a python and the throat it would just as fast wrap around, flashing with all the patterned trappings. Very rich, very not—everything out in the open.

Tenderness. The concept of it crucial in winter, crucial now.

Winter, when the bite of it comes, is brusque. We flee to warmer quarters, move away from prolonged exposure—to the world, its elements, inclusive of people—if you’re going to do anything then the onus in winter is quickly.

Up until three winters ago I would spend mine, once or twice a week, like a potato strapped on top of a 1400lb animal. Winter riding is a particular kind of self-inflicted torture. The thrilling and best parts of riding—feeling unencumbered by layers, bare arms, legs pressed against the body of a horse flying over a jump or just plain flying down a stretch as you lift your body by your own muscles and hover over a huge neck rounded enough that if you tilt you can see his giant nostrils flaring below—removed. Double gloved hands struggling for the softness of control that comes in holding, not pulling, a horse’s mouth but hands that go numb by frostbite anyway and when the blood come back it’s screaming, burning. You don’t ask for much because huge lungs, even when properly warmed up, are not fit for working in minus twenty below freezing. So you try and strike a balance, of making your body do most of the work to warm it up, and asking the horse to lend you some of its heat, some of its heart, all of its trust to be out there doing that with you right then. Its dark. Arena lights, at least the ones I have ridden in, are fluorescent and harsh if they are there at all. In a sport that is all about muscle control, muscle melding, fine movement and softness, the winter muffles each as if under layers of snow, caked ice, you find yourself using your voice more. Talking through asks. A good answer is the clouded breath of a horse responding in quiet, controlled work, a bad answer is silence.

The first twenty to thirty minutes are spent in tamped down agony, glancing at a clock if there is one, but like anything worth doing through effort there is a sweet spot you strain toward. Suddenly your body is flushed, heart pumping you warm, a horse under you listening, lighter, happy to be moving. It is so fleeting, barely there, because it is dangerous to push, to have the horse break a sweat, but the glancing feel of it through all the casing against weather, about a hundred layers of clothing, melts the moments. You hop off onto feet probably without feeling, ice blocks, the breath of the horse mixing with your own. Rest a hand on a giant neck and feel blood straining to meet yours. Riding anytime relies on asking another animal much bigger and stronger than you to work with you. Riding in the winter is asking, over and over again, laying yourself bare for hope, blood and heat, for jogging two brains into remembering what things will feel like again when it all finally thaws out.

And after the work is done, after you’ve cooled the horse out, brushed it down and double blanketed it, if the night is not too cold then you both venture out in the dark. Six legs plunging through ice-crusted snow, relying on the horse for balance. Nights I remember most were out under blue-cold full moons with Duke, floodlight bright spilling down over fields drifted high with snow and ringed by hydro lines, freezing, coyotes calling far off in the dark but the only sound both our steps, the huffing of him beside, maybe, as we got closer, the herd calling out, their shrill queries breaking the silence. He would rarely strain against the lead, would wait for me to take his halter off, put two bare hands against the sides of his huge head, humour me by butting my stomach with his nose strong enough I could feel it through a huge coat. When you experience something so huge being so tender—the night opened up in what feels only for you, an animal that big waiting on, for, you—you’re exposed. Broken down to your barest, maybe best maybe not, parts. What’s scary isn’t the feeling of everything else slipping away, it is knowing how little control you have over when it all comes sliding back. Even if trying for the feeling on its own doesn’t work, I think everyone has their own specific framework for conjuring up that kind of prone silence, trying for the result sometimes does. Trying for tenderness and hitting a bruise, hitting benevolence, hitting on what makes your blood call out, makes you happy, makes us human. Not hitting anything so trying, as best you can, again.