Summer League Forever VI

Eleven days in the desert; as always, an attempt to get it all down.

On the last day I walk to the arena. Desert softened by its own heat, evening light gone a flaring peach and colours washed to sage, lavender, crumbling ochre; me, softened by my own ferality from 10 days in the desert.

I use my teeth to pry the lid from a giant Dunkin’ iced coffee so I can pour the contents of a coconut water I’m juggling into it, no longer wondering what drivers scattered across Paradise Road’s six lanes think of a person, walking. I’ve come back this way from the arena plenty of times, walking headlong into the sun sinking behind the La Madre Mountains and evening spreading out across the desert, a dry sauna for the brain after six-plus hours in gyms filled with forced air and basketball. Out from those tunnels and crowded concourses into air shimmering with heat and roaring with jets landing practically over the shoulder, a few lonely palms and oleander shrubs blooming along the service road shortcut back to the hotel.

I’ve never approached Thomas & Mack this time, this way. Watched it rise silver and gleaming like a monolith from the desert, first vibrating like a mirage then forming solid and staunch, a mecca against acres of parking lot. Now the sun drapes across my shoulders, casts the blacktop a rich bronze. At my back, too, the jokes made by those who’ve left, usually in the hours before their leaving, on how I’ll survive so many days. Wishing luck and fortitude.

In the years my stays have extended I’ve learned these tidings are for the person saying them, who’s leaving. A benediction. I’ve also learned you don’t arrive to the desert with either luck or fortitude, but that when you stop counting the days you’ll find them rising to meet you. What was roving and desperate comes soft to your hand, offering its head.

In the desert you learn supplication shifts to form.

We talked about being swimmers. How he recoiled when his friends told him you could get underwater headphones now.

That’s for going through all the fucked up things in my head, he laughed.

I told him I tried to find a pool on work trips, but Vegas was a lost cause. All the pools set way out in the suburbs. Now come on, he said, lightly slapping the airport foodcourt table we started off sharing as strangers but over the course of our overpriced salads had learned of our professions (him: professor, me: writer), notable neighbours and now friends (him: Dr. J), and hobbies (both: swimming).

I could see him type a lengthy query into ChatGPT: Where in Las Vegas are there public pools for lane swimming? He showed me the map on his phone’s screen, a half dozen pin points all way out in the desert. Before he left for his gate, and after we talked about his former Georgetown alumni, Allen Iverson, hopefully growing easier with himself, he playfully wagged a finger at me. You get to a pool, now you know where they are!

A feeling like, here’s the trip starting. Here’s the person Summer League sent to auspiciously send me off.

What’s the feeling — hard to name. Broader, warmer, looser than anticipation. A sense of touching very lightly something living, feeling the tremor of recognition run down its body from that touch. All the people that’ll be there, their expression when they first see you; when you wordlessly watch the distance and time from, likely, last summer to this pass between you. A beautiful, dutiful collapsing; understanding of life in a glimpse before it rockets away from us again.

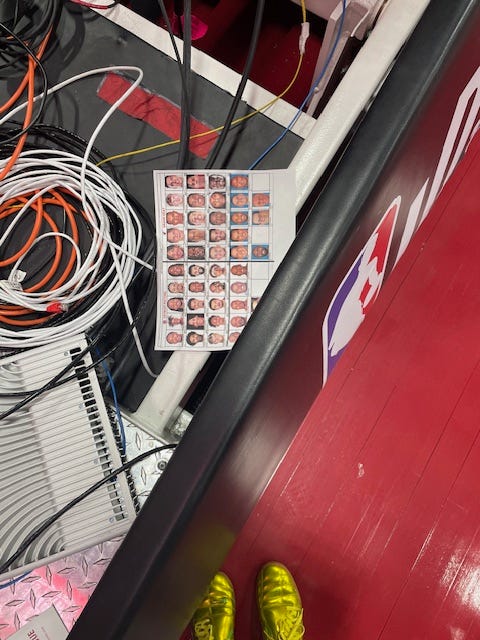

At the baseline in Cox, Paul George takes care with his feet over the coil of camera and other wires snaking to and from the basket’s padded stanchion. Loose printouts of stat sheets and roster pages with player headshots tucked around the stanchion’s base, used at a glimpse and then cast off, forgotten.

Dan asks him if he’s been to Disney lately. With his feet safely set on clean hardwood past the snarl of cables, George glances back. He clamps a hand on Dan’s shoulder and smiles at us both. Not lately, he laughs.

The rhythm, I think, I forget most. How it’s been six years and counting but I struggle through the real-time realization every time that it takes at least 24-hours in the place, split individually between everyone you hope to see or sit with, have your heart settle against, to sync to it. The sadness of that hits immediately though when you realize how flawed the math for the people who only stay two days. That by the time you feel like yourself against the banausic thrum of the city, the yawning pull of the desert, they’ll have gone.

I try to claw down the time best I can. Shave the hours off; wrestle as many as I can into waking hours, muddying the concept of waking hours with enthusiasm. A lousy trick anywhere but here but here, a whole city founded on the impulse.

Kenny Atkinson telling a roomful of my students something he’s noticed: they don’t believe in luck in the States.

He doesn’t say it like it’s an asset.

The Raptors first game in the big arena, sitting down at baseline seating with what feels like 40% of Toronto media. Jerome has brought me a Blizzard, Keeks is walking me through the algorithm she’s coded for stats, Doug calls playfully to a very tall figure suddenly leaning down to greet Wayne Embry, seated courtside, Down in front!

OG Anunoby turns to the voice, then the entire row of us, grins. Reaches for each of our hands. How’re you doing? He asks me. The fuzzy feeling of familiarity, of homecoming, suddenly so strong that I flush, have to stop myself from squeezing back too hard.

The place sloughs away at you. You lose sleep, hydration, any sense of boundaries. Become a soft composite. Tender. Too tender for the landscape, the heat. A compulsion of wanting to lean into every body I know, touch and be touched, their pulse a sturdier scaffolding for my own, grown ragged.

In bed sending voice notes back and forth with Seerat, who has to be up for a flight to Indianapolis for W All-Star in the same short number of hours I’ll wake again with the desert.

I describe to her the strong, strange tides of communication in this place. One, a wave of attention, flattery, funny and clumsy, too sharp if it weren’t for Vegas’ buffing; the other an ebb yanking at my ankles, threatening to topple for the sudden destabilizing rush. She sends back worries for her weekend, follow-up questions, a steadying clip of shit-talking. I can see the lights of the Strip in the distance, have yet to pull the blackout curtains against their persistent glow and thrum. I love you bro, she sends. I love you brooo, I say back in the dark. The notification comes that she’s kept the audio message.

In a car one night, the both of us en route to different dinners, I tell the head of basketball for one of the biggest agencies in the world that I don’t think this place is going to be around forever. Its encroachment, the mountains gnawing nearer, the reality of water, of climate. It’s not made for the long game, I say. You really think so? They ask, voice piqued with a hint of worry.

I realize when they asked what I thought of Vegas, they meant in polite opinion, inquisitive but still backdrop conversation. They didn’t mean what did I make of the place in the whole lore of human history.

I like weather, Phil says, phone line crackling. Not the exact same thing every day like this, it makes it even harder to tell one day from the next, he says.

I think to tell him that the day before I watched from our classroom windows underneath the arena as sand blew up in a great wall of wind and rolled over the UNLV buildings scattered to one side of Thomas & Mack, but remind myself that’s not weather — though most of the weather through the week is wind.

Sudden, desperate gusts, curling warm caresses, huge plumes that come rushing from the desert to billow sand up against bare legs. Rooftop at The Palms, wind comes up over the smudged glass safety wall, giddy, spilling across the club’s outer deck, crashing the party. Wind that steals my breath or else shoves it back into my throat. Wind, pummelling, grasping, swallowing; wind, fleeting and full-on as the rest of it.

Two days after our call the clouds roll in. Flat bottomed and whipped up tall, white as promise, the mountains corralling them in and the sun, somehow, streaming down unfettered.

Did you see the clouds? I text Phil. Lol, I noticed, he replies.

I make a daily habit to go and take the seat closest to the basket in Cox when our classes have wrapped for the day. I sit for five, maybe 10 minutes depending how the game is going, waiting for the sun outside to sink a little more or the game’s energy to turn erratic — whichever comes first.

Sometimes Warren appears, checks in and rests his elbows on the table, responding to the never-ending stream of messages on his phone while players thunder down the floor toward us. Other times I feel my pulse sync to the thud of the ball, squeak of sneakers, drone of the buzzer right above my head. Feel my eyes hood, shoulders relax, even as guys hit the floor or come flying out of bounds beside me, so close I can feel the heat shedding from their bodies.

After 7pm in Cox the gym gets so quiet you can hear every word from both benches, can hear the slap of skin on skin contact, the sticky sound of bare arms and legs pulling apart; a baby in the crowd crying out, sharp and urgent, just once.

Comparing hours of sleep with Austin Reeves. I got five, he says. Solid. Ah, got you there — three, I smirk. Exhaustion vibrating in my body like a prize.

The entire ecosystems that spawn to support each game.

Security, interns running stats, a collage of current players from either team there to support in their soft summer clothes. Even alongside LeBron James in a bucket hat looking glum, it’s the kids on ball crew I notice most. On hands and knees towelling off the floor, or carrying plastic trays with individual tiny cups of Gatorade during timeouts that they’ve carefully lined up. Their attention, as they weave around the towering and heaving bodies huddling close to their coaches, entire.

Brooks Barnhizer, before each free throw, telling the ball to Please, get up.

On the concourse, comparing greys. Can you see mine, right here? I ask Howard, lifting a section of my bangs. I can’t, he says, moving to squint, Not at all. Soon, someone from the Knicks front office walks over to see Howard, introduces himself to me. Unaware of our search for age as his team takes the floor and plays against the seasonal backdrop meant to highlight how green they are, practically shining.

One of my students, responding to my critique about her game recap assignment, says she pictures a male audience, for some reason, when she’s writing about basketball. She simplifies, streamlines. Kills off what comes natural and more expressive. She has broader, livelier language — I’ve read it — but holds it back thinking about this critical, composite reader.

I have to tamp down hard on my initial surge of disdain — not for her, but the impulse and the audience that’s created it — temper it to something useful, not overwhelming. That instinct, to put what you’re seeing and how you’re seeing it down, that’s all I want, I tell her. Don’t bury it, don’t write from down here, I draw a somewhat shaking hand flat down across the tops of the empty arena seats a row in front of us. We have enough of that for lifetimes. Go up.

Harrison and Mia stick around as the gym empties to watch me watch my students do postgame interviews with James Wade and Alijah Martin, watch me try not to hover and take too obvious of photos as they carry out the most polite scrum I’ve ever seen.

When we leave the arena to get dinner, spitting rain. The heathery, overgrown willows at the base of the Cox stairs bow over the wall in supplication. An hour later, deciding to walk from tiki bar to taco shop, down comes rain. Real rain. The smell of asphalt, gasoline, sage and wet dirt hanging in the air. We’re the only people we see, streets between plazas wide as the highway we can see, sluicing toward the Strip. The rain, the air, our faces, all flushed.

Sitting in Holland and Taylor’s film screening, right off the concourse. I try to count the days since Adam Silver took the same stage in sneakers and athleisure to welcome our SBC students, use my fingers to count back six. The next morning I’ll be editing writing assignments in the same room, empty, glancing up to the floor to ceiling windows each time a plane slopes in to land.

A buzzer sounding in a scene of their film syncs exactly with the buzzer from a game in T&M, cutting up through the concourse, and forces me to the present — grinning in my seat, feeling so proud of my friends.

A passing security guard with a giant pretzel. Not thinking, I blurt how good it looks. Here, he says, tilting it toward me, take some. I tear a piece and he changes his mind, says, Go on, take the rest.

J.A. and his backpack full of Red Vines. His serious advice about Red Vines. Make sure they’re the light red ones, he stresses, those are the freshest.

Julie at dinner on the last night, loading my plate up with her appetizers because I’ll have to split for the Psychedelic Furs show before the mains come. A giant shrimp and a giant meatball, now doubled. You’re going to be dancing and having a few drinks, you need to eat, she says. I picture her doing this for Charles Barkley, Steve Nash, Devin Booker, across a 40-year career.

Rob with our breakfast sandwiches, waiting for me. I come into the casino’s food court at a different angle, getting to see him from the side as he keeps a continuous scan of the door so he can wave me over. Excellent posture. At my place there’s a canned coffee and a cup, ready for ice. Kills me. If not so voyeuristic, so incredibly indulgent, wouldn’t it be nice to witness the people we care about in the moments just before we appear? Primed for us, in all our ragged glory.

Off in the distance, beside the big High Roller ferris wheel baking in the sun, a drifting shape. I stop writing and squint, lean forward to get a better look out my hotel room windows. The skinny palms clumped around the pool toss in the wind like horses throwing their heads.

A bird? But then I realize I’ve never seen one winging the Strip, under any sky. The shape shimmies, suddenly slips vertical down through the air. A balloon. Way out and up there. I watch it ‘til I can’t see it anymore, wonder if anyone else out of any of these thousands of windows rising from the flat pan of desert bedrock is watching it too. Wonder if it’s popped.

Sitting in an otherwise empty media row with Duane for the Raptors qualifying playoff game, my attention drifts for a second, comes back with a warm snap to the sound of Duane kissing his teeth at a bad call. I echo him. Instinctual call-and-response. A familiar sound of home when everyone else from Toronto has long left.

In the hotel’s shallow wading pool on day 10, lying nearly flat on my back to be able to submerge up to my chin in the water. It’s so hot that the binding glue in the novel I brought out to read under an umbrella melts, releases the last 20 pages of the book to go fluttering over the baking terracotta tiles of the pool deck.

I close my eyes under sunglasses as Robyn’s ‘Honey’ thrums from the speakers rigged up in the palm trees. Feel like some exhausted crocodile, predatory but entirely defunct. Open my eyes and they snag on the only clump of clouds in the cornflower sky, shape like teeth marks indenting all that impossible endless blue.

Halfway through the 2nd quarter in the Finals game a pass goes wide, sinks easy into the lap of Mason Jones, sitting on the Kings bench. His hands slip instinctively around the ball. There’s a whisper of contact, palms on pebble. Kings’ ball, the announcers call. Indeed.

I flag the 4 Queens bartender down to make another Long Island Iced Tea and Julien stays my hand. Gently but physically presses it down onto the bar top. I wanted to get one for Kyle, too, I tell him. Julien shakes his head. For me and Keith, you know we’re fine, he says. Anyone else, you need consent.

Something hopelessly tender about the last day. Coming up the little elevator and seeing for the first time Cox completely struck, empty. Sad, isn’t it? An intern says, sidling up beside me. I’ve never seen it this way, I say, a little dazed.

The concourse sparse but electric. Familiarity bursting, everybody tired, talkative.

After the Hornets win, Kon Knueppel comes out for his postgame holding his MVP award and wearing his credential. I’ve never seen a player wearing one and something about it — that he might be mistaken, misdirected, barred or shut out — is too sincere for the tunnel in its funereal process. Cords are being expeditiously looped, curtains pulled down and folded, cameras shut away into rolling cases, even the pop-a-shot games are being deconstructed by hand, small balls individually wrapped. NBA PR motions for him to take the credential off for his interviews and he ducks his head hugely to do it, fiddles with it.

I can see down the chute to the court where dozens of interns are busy rolling banners in unison, Summer League argonauts. To see the teardown is almost too much. I’ve only ever arrived into the place, full of promise and expectation. This feels like picking the carcass of an animal clean.

Don’t cry in the tunnel, I will myself. Save it for the desert at night. Minerals and moisture offered up to the hills like a gift.

It’s pure, the coach from Belgrade says, sipping Rioja from a plastic cup. We’ve both wound up at the wrap dinner, Summer League trophy just hoisted down on the court and awards being handed out to the interns who keep the entire event running.

He shifts the conversation. Ayuasca, have you tried it? I see your tattoos. He nods, he means I am “alternative”. Maybe you’re feeling closed off, he says. It’s a good thing for that.

I don’t have the heart or vocabulary just then to explain being so open, essentially a sieve for this place, is what gets and keeps me here. Though in that moment, not so much closed off as necessarily quiet at a table in a room full of 100 or so Summer League interns who’ve just spent their last hours packing up what they built: the merch stands, concourse activations, an entire arena, loading all of it into trucks; gathered now to queue for family-format foil containers of congealing pasta and meatballs and celebrate their peers, still somehow converting their exhaustion into surplus energy.

How open I feel will force me to slip out after dinner, as goodbyes are being said, and walk back to the hotel alone at midnight to get a handle on myself. In the process I’ll pass the UNLV field I love to see being watered by sprinklers early each morning, balm to the eyes, and for the first time feel cool air wafting from the grass — from anywhere in the desert — green of it drifting over to meet me in the night. Heady, tender, potent.

It’s hard to keep things this pure, he says, nodding almost gravely to the room. But looking at the bright faces filling it, listening to their speeches and thanks and inside jokes to each other, I let myself stay suspended a little longer in the feeling that it’s easy to maintain with care as a baseline.

At my gate, waiting to board, a nearby bar starts playing ‘Band on the Run’. The call for my zone comes as Paul McCartney begins to drone, If I ever get out of here. A taunt, a dare.

Ok, ok.

A read unlike any other, and quite fun. Thanks Katie for taking me to SL!

Nice!