Hasta luego

The last three nights have been waking up at 3am with the full moon spilling in through the window, bright white glowing like milk in refrigerator light across the bed, and listening to four different sets of lungs in close physical proximity regulate the bodies they are buried in. The tinge of animal breath and Dylan’s and the window cracked an inch to fall finally dropping to single digits, feeling a dog’s body against my shins and chasing off, gradually, whatever thought it was that rocked me wide awake—goodbyes, mostly. The kind of exits that you cannot guard against. That go all down your spine like a mallet to xylophone bars, one at a time.

Last Friday night in Mexico City I got so sick I was up every half hour on a timer my body had set to revolt, puking with such violence I couldn’t breathe in between heaves. The apartment was on the 3rd floor and the beautiful mercury glass windows of the bathroom opened to an interior shaft down to the lower two floors, flourishing pothos and split leaf philodendrons sitting on white washed ledges in giant clay pots the only company to the sound of my sick echoing up and down it all night. I’d take small sips of water from the volcanic rock filtered cooler in the kitchen before I made my way back to the apartment’s couch for my 30 minute reprieve before the next bout and listen to the clock tick down the hours, willing the morning to come like it would burn off my state with the dark, feeling so sure daylight would set me right.

The next day, emptied but determined not to lose more minutes to lack of control over my body, Dylan and I went to Coyoacán to see Frida and Trotsky’s places, respectively. I had the luck to be at Casa Azul this past February, but even with that under my belt, the speed at which we went through the honestly magical rooms of the compound were lurching. I heard myself as a tour guide mumbling over words that came out like incantations as I swatted the air by way of indication, “Taxidermied giant sea turtle”, “Trotsky’s dinky bed”, “Noguchi's butterflies”, “death mask”, “actual ashes in giant clay frog urn”, “gift shop” before we let the exit turnstile bump our hips out into the street.

At Trotsky’s compound I got worse. Leaning into a bunny hutch for courage and watching maybe 11th generation Holland lops munch lettuce leaves while I willed my stomach to decide, was it going to let loose here or not? Growing more frustrated with myself by the minute, the walls riddled with bullet holes from assassination attempts but I couldn’t pull the trigger to make myself puke in one persecuted communist’s rose garden?

We pulled the plug and retreated back to the apartment. The restaurant on the main floor sent up the blandest food they could—pizza—and we watched The Perfect Storm, Frida and, perfectly for how it made me feel at least a bit more stable, Outbreak, before I fell asleep to the vaquero band in the street below the bedroom’s Juliet windows.

The next morning, like the morning I had believed in so feverishly the one before, came on like a cure, my body having come back to me in the night. I could finally recall the day that had set it all in motion without pulling the release leaver on my guts: overheating in the Zócalo, echoing around an empty National Palace, pointing out my favourite ancient uncovered jaguar heads with winding serpent bodies chilling in Templo Mayor pyramid that the city uncovered digging a subway in the 70s, drinking micheladas and mezcal margaritas at bars with saloon doors in from the wide, body-clogged streets, drinking draft beers in chalices big as my head at a bull fighters bar, swaying with the sun bouncing into my eyes from the glass building across the street reflecting me back along with the crumbling statues from the 1600s on precipices above me, leaning with me into the cobblestone streets.

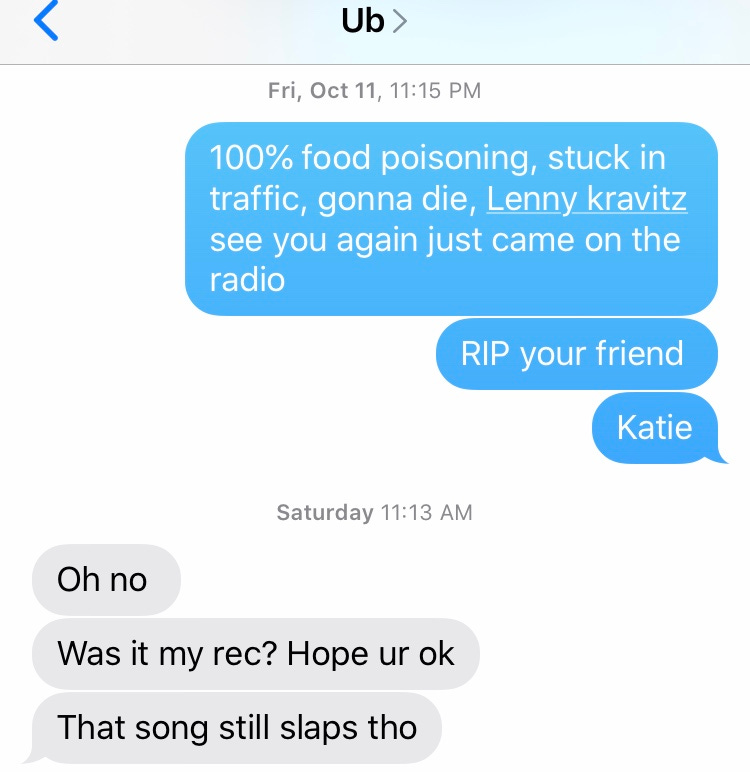

Walking to Rosetta in a torrential downpour, trying to focus on the menu as whatever took hold of me for 24hrs was about to, climbing into a car back to the apartment with Lenny Kravitz blasting and texting Yusef to tell him maybe it was the bullfighting bar he recommended us that did it but also, how cruel it was to hear ‘Again’ and not be able to laugh.

“I think when you are truly stuck, when you have stood still in the same spot for too long, you throw a grenade in exactly the spot you were standing in, and jump, and pray. It is the momentum of last resort.”

That Renata Adler quote is one I’ve turned over like an engine too many times to count, softening it around the edges at every desperate moment I’ve reached for it, but every time I have needed it I find it fresh.

I quit this week. There is a rush to quitting, no matter how long it has been coming. A kind of sudden clarity like a fresh nick in the skin running impossibly bright blood before it slows and sear sets in or a deep, deep breath at exactly the right time. Either by virtue of the decision itself or because a decision was, finally, made. Quitting is cutting a cartoon exit door in the canyon wall where you otherwise may have died of dehydration. Quitting is weighing your value against the thing, maybe at the moment, cashing you out and deciding something is not adding up. Quitting is handing something over you weren’t done with yet and acknowledging that chances can be better than a thing proven.

Sometimes, willingly detonating a part of your life is a kind of self protection. Even if it was not how you imagined things going, or going out, there are moments when making the choice to end something can be tender.

A friend of mine, the kind of friend you count as fluke, as lightning struck strong and fast enough to kill you but instead will settle comfortably across from you and tell you encouragingly all the times you are being foolish, made the choice to let something go from themselves this week that words like ‘courage’ could not expand far enough to cover. As they went back and tenderly gathered up the enormity of the parachute that had supported the weight of this exit, just to unfurl it again for me, I traced a finger across the skyline of downtown Toronto spread out before me in the window of the stairwell where my voice echoed back up to me with every word that could not hope to match theirs. A train rumbled past outside and the wind violently curved the tops of trees in shapes like living bodies and my friend’s voice cauterized their sounds with its precision, its clarity, its force. How considered, this impossible thing they were saying, how much I could hear in it the patience of someone who has just watched the very bedrock of their life lift and burst and decided, still, to wait for it all to settle where it will and to try to build on it again.

Your world can end so many times, so many ways, but it won’t, not really, not until it finally does alongside you. What you learn from all the endings is that the beginning is always right there, waiting.

Here’s what is happening, less than five days before basketball starts in earnest: China is gone or isn’t, is gone for now, is gone in as much as a tiny tremor has opened a rent in the world of the league’s relationship with it. China—because that is how we refer to one situation in basketball now—demanded Adam Silver fire Daryl Morey and Silver said, apparently verbatim, “No chance.” Because in a turn I’m not sure Morey would ever have considered his life taking he is now the symbolic start and would-be end to something so much bigger, a deluge there’s no damming of though plenty of damning of, probably, over hissed calls and closed meetings in Secaucus. Another deluge there’s no damming are the karmic repercussions befalling the Clippers organization, presumably, from signing Kawhi. You get the flood you pay for, is all. LeBron has turned human in that he is capable of making a dumb, not considered as in wasn’t even thinking about it kind of mistake. Has shown what he doesn’t know which is as much as any of us: a lot. Mario Hezjona posted a video through a car windshield drawing closer and closer to Mount Hood in the distance that felt mythic in the way that remembering there’s ways in which the world will never stop dwarfing us will. Buddy Hield put himself in a mountain’s position saying he “wasn’t going to budge for nobody” when it came to collecting what he wanted, what he’s worth, or else he had no qualms about getting the hell out of Sacramento. Vince Carter sat on a courtside video screen beside RJ Barrett and somehow, to the naked eye, swapped their physical ages. Nick Nurse turned into the sherif who rolls into town wearing all black without a speck of desert dust on him and called out, in a quickdraw firing of “Nope. Nope. Nope”s the guys who aren’t digging, aren’t creating their own exits on court, don’t have a taste for the particular blood coursing through late-October. Kyle Lowry got the bag. Pascal Siakam is probably going to get the bag. Harrison Barnes has quietly offered to finance the impossible, or, what seems impossible only when your privilege draws lines as sturdy as walls to keep these kinds of possibilities out.

And this is, all of it, still outside the scope of actual basketball. On the exit of the offseason it is important to remember all the things that can get framed merely as anomalistic events we are toiling away the time with until the season starts, versus these things being the thudding pulse, less a ball, of a game played by actual people. People who fuck up, enormously, make mistakes, or who are tender, who show confusion and vulnerability. But all of it, the missteps, real-time deterioration, the outbursts, an honest representation of a league that won’t ever be, however much you want it to, just one thing.

Basketball is starting, yes sure, but the lives in its orbit have not been holding their breath this whole time. Zion isn’t dead.

In Mexico City I got into the habit of using my loose, not great, small familiar snatches of Spanish. My favourite is hasta luego. As far as goodbyes go it’s perfect. On it’s own, hasta/until, luego/then, but together something even better. Non committal, casual, tender because the implication is that you’re going to see that person later, no matter if you already know it to be impossible. Cab drivers, bar tenders, shop keepers, servers, gracias and hasta luego. Thanks and see you later. Present perfect as far as I’m concerned.

It’s not like you couldn’t make a habit of saying this in English to strangers, but the inherent knowledge that you most likely won’t makes it seem juvenile, underscores it in crayon. There is a formality in English that prevents this kind of open ended expectation, almost a wish, in the way we structure our ends and exits. Goodbye, bye, farewell (but who says farewell verbatim), so long. So long is the closest, and even in that there’s an implied distance both people must either physically travel or allow to pass before they could hope to see the other again.

We want to mark our exits from each other dramatically, sincerely, as something final, instead of encouraging the option that they might not be, that we never know. That we can embrace the unknown and that in itself can be casual. That we can promise, hope for something unrealistic, have an expectation or none at all. Until then or see you later, an exit with a start, an end with a beginning already on the way.